By Daniel Rose

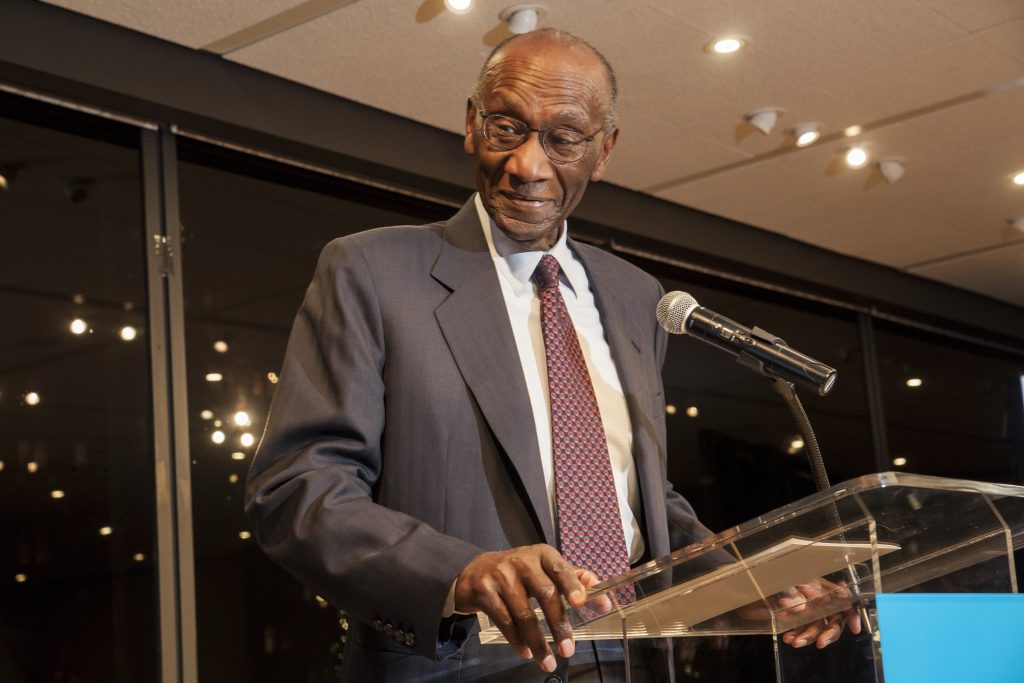

In a society currently abounding in moral, intellectual and spiritual pygmies, and with painfully few appropriate role models and mentors after whom young people of high aspirations can pattern themselves, the exemplary life of Franklin A. Thomas merits widespread acknowledgement and discussion.

Thomas’ excessive personal modesty, reflected in his invariable insistence in giving credit to his colleagues and ‘teammates’, has concealed or obscured the true stature and achievements of this authentic giant of our times. His recently-published memoirs, “An Unplanned Life”, is a ‘must read’ for those wishing to see our society in perspective and who hope to help it regain lost momentum toward goals of justice, integrity and compassion.

Born in Brooklyn in 1934 to penniless but aspiring immigrant parents from the Caribbean (his father from Antigua, his mother from Barbados), he was the youngest of six children who were raised to believe that with good life values, supported by education and persistent hard work, they could realize their human potential.

Highly motivated from early childhood, Thomas excelled both as a student and as an athlete; and a scholarship to Columbia University (to whose Board of Trustees he was elected in 1969!) enabled him to flourish as both.

In his senior year he was both Captain of Columbia’s varsity basketball team and a prominent member of the R.O.T.C., the then-required military training program. This led to his outstanding career with the U.S. Air Force, in which he rose to the rank of Captain.

Next came his years at Columbia Law School, from which he graduated with ‘moot court honors’ in 1963. This led to an offer by Robert Morgenthau to join the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York, where his colleague Vincent Broderick – on later becoming NYC Police Commissioner – offered Thomas the position of Deputy Commissioner.

When John Lindsay became New York’s Mayor in 1965, he accepted Thomas’ resignation as Deputy Police Commissioner and appointed him as Executive Director of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, announcing “my administration’s commitment to put our very best talent to work at the key job of rehabilitating and upgrading the city’s neglected neighborhoods”.

Thomas initially agreed to the leadership of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation for two years. When he left ten years later, what had been accomplished – in physical development, economic and business development, cultural and social community-based programing – was legendary. Thousands of jobs and many business start-ups were created, and hundreds of new and rehabilitated housing units were provided, along with a mortgage pool investing over $20 million in others. A $6 million shopping center, including 115,00 sq. ft. of retail space and 60,000 sq. ft. of office space, as well as a 30,000 sq. ft. open plaza and a 8,500 sq. ft. ice skating rink were all part of a true community center in the heart of Brooklyn.

At that point, then-President elect Jimmy Carter offered Thomas the role of Secretary of H.U.D. but Thomas turned it down, feeling that it was not the right role for him in his final years. Already a director of prominent corporations – Citibank, Alcoa, PepsiCo and others – Thomas accepted an invitation to join the Board of the Ford Foundation, an organization with severe problems. When he eventually left Ford, as President, in 1994, the organization’s transformation had been prodigious. At his arrival, in 1979, Ford’s assets were $2.2 billion; when he left, they were $7.7 billion. Annual spending had grown from $119 million in 1979 to $420 million in 1995. During his term, a total of $4.2 billion had been expended on Ford programs, and the staff had decreased from 800 in 1980 to 550 when he left.

In his final years after leaving Ford, Thomas made the democratization of South Africa his major concern, with many visits, repeated meetings with his friend Nelson Mandela, endless conferences and, finally, his chairing the prestigious study committee that produced the highly regarded manifesto, “South Africa: Time Running Out”.

My personal relations with Frank Thomas were cordial and mutually respectful. A garrulous person like me, however, found that his soft-spoken, brief and concise comments precluded extended conversation. My friends Bob Morgenthau, Cy Vance and Colin Powell endlessly sang his praises as one of the most remarkable individuals they had known, and I concur. Frank Thomas’s formidable record speaks for itself, and a broad audience must listen.