Artist, Philip Smallwood, defines the state of art, race, and progress.

by Marlie Messena

Ask the average American about their favorite artist and you may get a bashful look and an embarrassed mumble. What about a household name in the art world? Likely Picasso, possibly Monet or Michelangelo. The more cosmopolitan may be enthused to share their knowledge of names like Hirst, Koons or Haring. What these artists have in common could be likened to the similarities of the world’s most well-known CEOs or politicians; there is a racial and gender divide the likes of which is normally reserved for STEM programs and Ivy League economics theses.

And yet art has been the hallmark of every great generation, society and culture, the story tellers of history and the gatekeeper of future tales. Why then, can we not walk into any museum – from the storied halls of the NYC institutions to the community-run suburban art houses – and see an equal representation of what art has to tell us about the societies that have paved the way; for the artistic visions of the generations that have taught us all we know about the brushstrokes, clay sculptures and everything in between?

The painter P. Smallwood, known for his signature paintings termed, “Lifescapes”, shares his thoughts on the matter. While he has long eschewed the label of “black artist”, he does question the lack of representation in the art world. The truth is that less than 8% of the public buy original artwork, meaning that the competition for representation, exposure and sales, is fierce among the most talented. Even more so when underrepresentation is a significant barrier to entry to that much-coveted clientele.

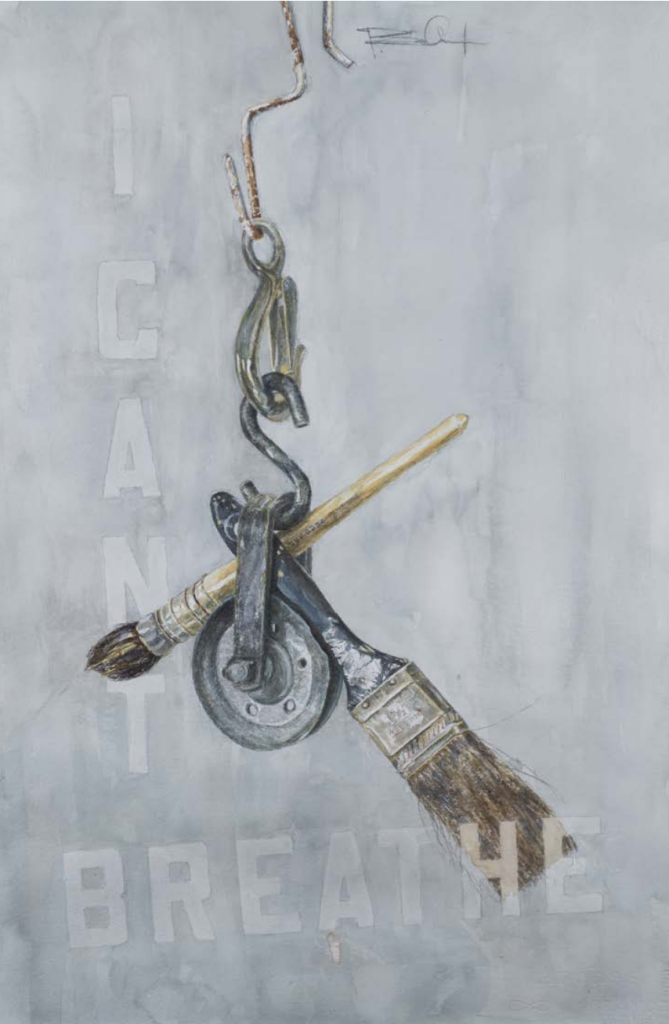

If you think that you can’t turn a corner in any American mall, street or cafe without catching a glimpse of that ubiquitous Basquiat crown means that we have now entered the “post-racial” era of the art world, think again. “There are hints of tokenism,” Smallwood notes, “we are highlighted in exhibitions that at times feel like token exhibitions. Museums will often acquire pieces from larger exhibitions for their permanent collections, but that isn’t happening at the same rate for African-American artists.”

It would be simple to dismiss this as one artist’s anecdotal thoughts, but a 2019 study from Williams College confirmed what many have whispered in their own circles for decades, most US museums are only showing art made by White men. Researchers found that just 1.2% of works in permanent collections were that of Black artists. This is the lowest share of any race.

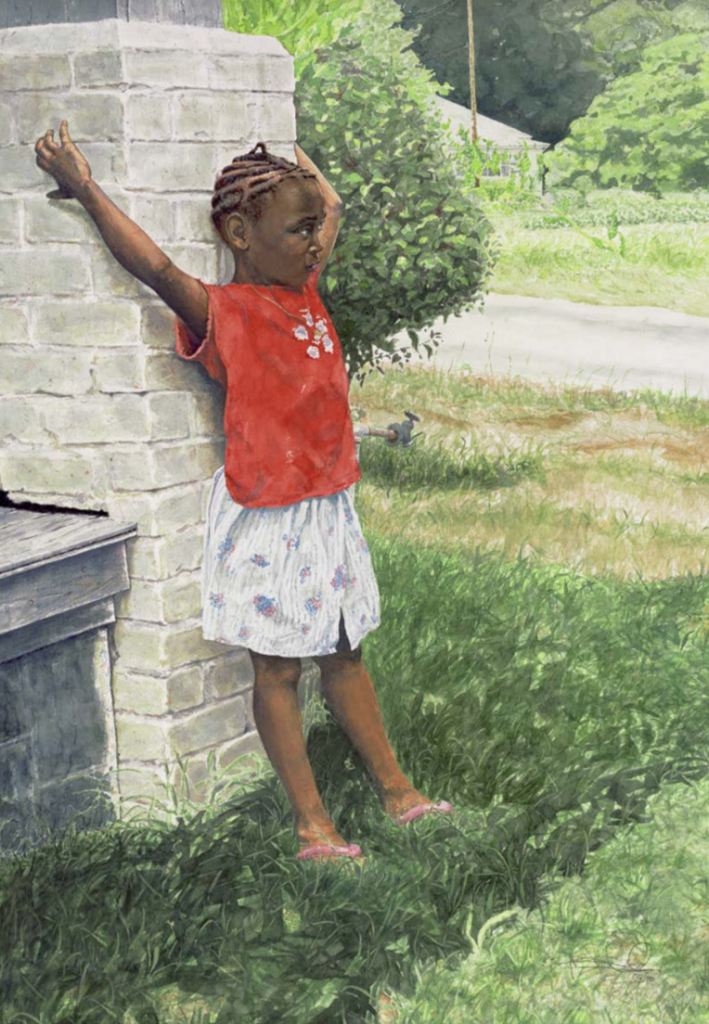

And while this fact may elicit a dismissive eye roll from many “not again-ers”, the fact remains that representation matters, perhaps especially in art. Art reflects our lives; from photographs of the perils of the civil rights marches to the ancient traditions of civilizations, these visual reminders are quiet whispers from our ancestors reminding us…”we were here.” And if this history can be so easily dismissed, what of the reflection of everyday American, from the sweaty Bronx summers with illegal fire hydrant scenes to wheat-covered “fly-over” communities that evoke such pride? Especially to an artist like Smallwood, whose portraiture and visual narrative reflect the life around him, and yes, whose clientele is mostly non-black, a result of a very intentional representational decision. “It’s just now that I am building up a more African-American clientele, many of whom are surprised that our paths have not recently crossed,” notes Smallwood. Black artists are many, black collectors, much less so.

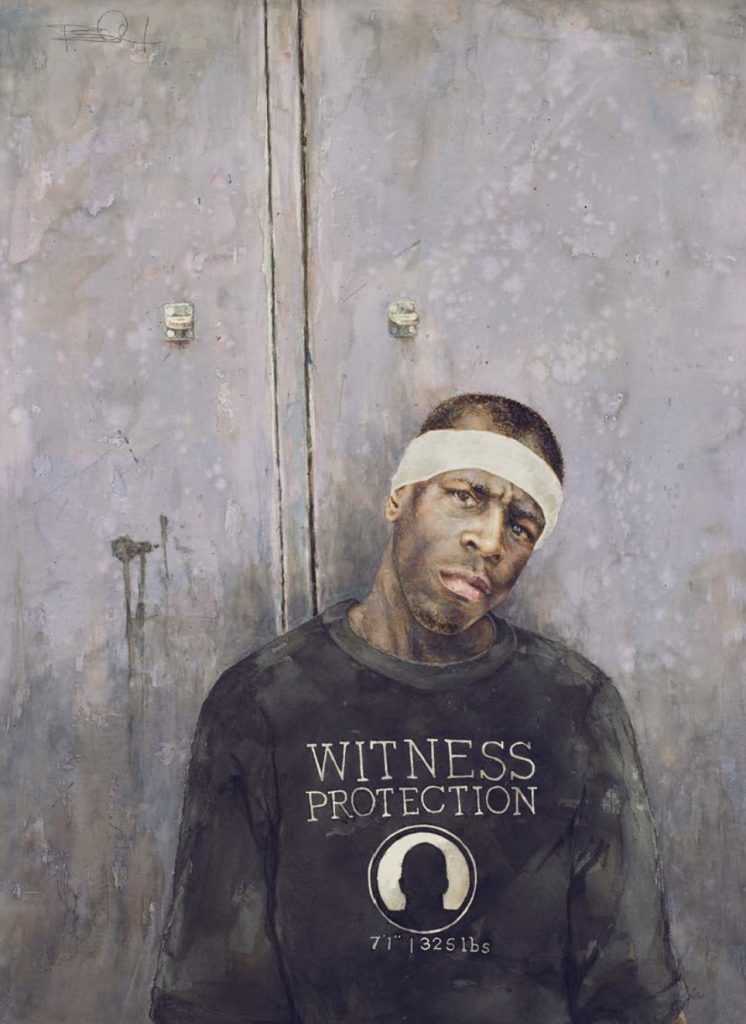

“The art allows a barrier to be broken because there is a conception coming in about what you are and at what level you might be doing it,” says Smallwood. And yet, many of his clients may note that a particular piece reminds them of a family member. “The work goes beyond the preconceived limitation. It is a level of communication. People can feel these people in the artwork and form an emotional connection to the work beyond what’s in front of them.”

And so, are we to expect a “Me Too” or “Say Her Name” level backlash from the artists that the many art renaissances have left behind? “It’s getting better,” notes Smallwood, optimistically. There is an education to be had on all sides, and he would like to be the artist that people can come to for casual advice. It’s not about having made it, but rather having made a way. A seat at the table or perhaps a painting on the wall, so to speak?

And it does start with an education. Smallwood recommends starting in your community. Visit student shows, support your local artists. There is this perception that “true” art is unattainable, which yes, does feel like an exclusive barrier to entry. Smallwood counters, “you could buy original artwork for $200. And it doesn’t have to match your couch,” he cracks, “ just buy what you like.” A statement that seems so simple it feels almost elementary in its approach, and yet, there is often nowhere to start but at the beginning. Smallwood also references the documentary “The Price of Everything”, “in our society, if something doesn’t cost a lot, it has no perceived value. But the only value that’s necessary is what it means to you.”

And what of the value of a Philip Smallwood piece? If the investment in art remains an industry challenge, why not make art for the masses? “I do this for the people, why would I cheat the people. It’s a long, difficult process therefore expensive.” As many creatives have long noted, “you aren’t buying just today’s piece, you are buying a lifetime of experiences and learning, that have culminated in this piece, after all “if i can’t excite me, I have no prospect of exciting you.”

In the midst of all this, there remains a current of greater inclusion. And though it may be a result of external pressures, a recent attempt in many areas to right long-standing wrongs, progress at any rate, is progress. Does a black artist create black art? Is the differentiation itself a benchmark of this progress? Have the arbitrary gatekeepers and arbiters of what is art had their antiquated moments? In this era of social media and globalized thought, who is to say? And, as says the title of the 1967 song by Les McCann & Eddie Harris, “Compared to What?”