Anthony Whitaker first saw what remained of the fallen Twin Towers of the World Trade Center at night. It looked like a monolithic piece of art to him. Breathtaking at 207-feet high, the shell of the building’s facade was taller than the statue of liberty (which is 151-feet tall). Whitaker worked for Con Edison at the time, identifying damaged cables and locating the problems in Brooklyn and Queens. However, the island of Manhattan was on lockdown. Since he couldn’t leave the City, he was relocated to Ground Zero for eight days.

“They had these flood lights on it,” Whitaker recalls. “It was amazing. Just… beautiful!”

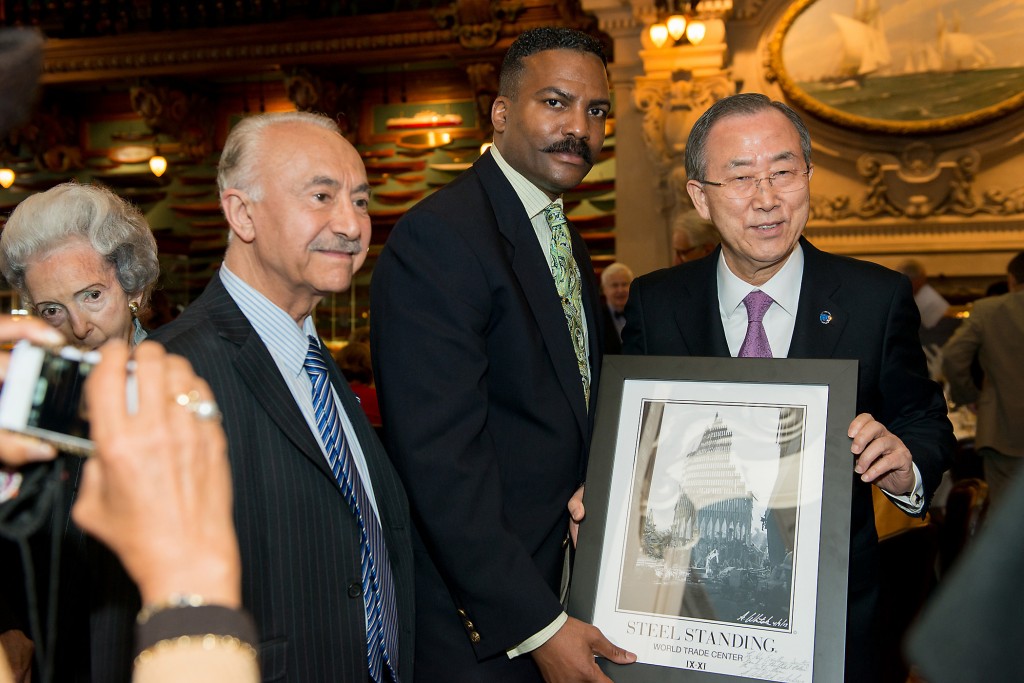

Like most people, the events of 9/11 impacted Whitaker on a personal level. In addition to knowing four people who had lost their lives in the attack, his dad had just passed away; he was trying to get a designer-clothing line up (as a follow-up to winning the National Association of Men’s Sportswear Buyer’s “New Face” Award in 1998), and he was feeling the pressure of being a young father. Standing before the rubble, he says, “I felt a strong sense of vulnerability, and I don’t say this often but I felt like it was speaking to me. It said, ‘I am steel… standing.’”

An artist, with an engineering background, Anthony Whitaker knew he wanted to capture the image but the area was covered by the military, hundreds of armed military-security men. Everybody was very

very tense, and he didn’t want to start a “riot” by using a flash. He admits he wasn’t really into the technical aspect of photography, he just liked the idea of composing an image. It compelled him. When he went home, he started sketching how he wanted to frame it.

The next day, Whitaker’s shift was 7:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m., and he was working in a different area of Ground Zero. There were check points, and even though he was with Con Ed, he could not roam around the area freely. He still had to be checked by the military. He found himself studying the structure from an artist’s perspective. He had studied symbolism, the shape and form was communicating with him, and he found himself thinking, “I know what I’m looking at, it’s a symbol… It’s a message.”

On the way out the door, the third day, Whitaker grabbed his Canon EOS 620 camera that he had bought in 1989, loaded with still film. (We hadn’t even gone digital at that time.) He says he took the camera because he thought, “It’s world history, afterall, right.” Still, he knew he wanted it to be black and white, so he took several rolls of film.

A professional photographer was on site, that day, and asked to see his camera. He looked at the settings, gave Whitaker a crash course on setting the camera for the optimum image, and set the camera for him to get a better shot. The real problem was that Whitaker had to be on a certain block to get that original perspective that he wanted to capture but he couldn’t remember where that was!

It took Whitaker a couple of days to figure it out: the angle he wanted was from the northeast corner of Washington Street. That particular block was usually heavily guarded but this morning, it wasn’t. It was the seventh day, the morning of September 18. Only two military men, armed with machine guns, were guarding the block but Whitaker was still quite nervous.

“A firewoman comes out of nowhere!” exclaims Whitaker. “I’ve never seen one before, and I haven’t seen one since. She comes up to the truck, and she says she needs a ride…” Whitaker remembers she offered to pay him, he told her, “Nah, nah, don’t worry about it. What I’d like to do,” pointing at the ruins of the Twin Tower, “is make a picture of that!”

Five minutes goes by. He took the color roll out, and put in the black-and-white film. “This it is. I’m just trying to get this ruin….I just wanted it for myself, as an artist…I shot six times, just in case it doesn’t come out. I hit rewind, and wasted the other 30 frames. I’m so excited because I got the shot!” beams Whitaker. (The remains of Twin Tower’s facade was dismantled the following day.)

After working 16 hours, instead of going home, Whitaker took the film rolls to the developer. He had made over 100 images. Later, when he went to pick them up, the old guy looking at the images–a veteran photographer of 40 years–complimented him on his captures. After a pause, he continues, “…But this one, this is a masterpiece! Sign it, and date it for me… This is a masterpiece.” They both agreed, the negative is almost as incredible as the image!

The phenomenon of art has remained a dark mystery, with little known about its nature, its function in human life or the cause of its tremendous psychological power. Yet, art is of passionately intense

importance, a profoundly personal concern to most people. Art tells us, in effect, which aspects of our experience are to be regarded as essential and significant. it is the voice of our sense of life.

Reflecting back on the “Steel Standing” image, Whitaker affirms, “…It had wings! People wanting to meet me. Newsday, The Post, wanted to do full-page pieces on it. Real estate companies were calling me in to sign posters to send around the country… I wasn’t sure how it was going to be accepted. But it took on its own life.”

Anthony Whitaker believes that the arresting image is more than a remembrance of those lost in the tragedy of 9/11, he believes the image gives honor to the spirit of courage, strength, resilence, and rebirth, that it deals with the endurance of the human spirit. Everybody has a “Steel Standing”

story of survival. The image continues to compel him: he thinks about it all the time, and has been envisioning a sculpture of the ruin for quite some time.

A number of years ago, a powerful wave of digital technology that is replacing labor in increasingly complex tasks rolled in. In 2005, academic journals had begun to report on the possible artistic applications of 3D-printing technology. This is a digital process for making a three-dimensional object of almost any shape from a 3D model or other electronic-data source primarily through additive processes in which successive layers of material are laid down under computer control. A 3D printer is a type of industrial robot. By 2007, the mass media followed with an article in the Wall Street Journal and Time Magazine, listing a 3D-printed design among their 100 most influential designs of the year. 3D printing captured Whitaker’s interested, and he started looking into it as a means of expression.

Whitaker has been developing the specifications for a three-dimensional sculpture of “Steel Standing” by a 3D-printer fabricator for more than two years. He is pleased with the results: the precision of the software that is creating his design is impressive.

It’s almost ready for output. The use of 3D-scanning technologies allows the replication of real objects without the use of moulding techniques that in many cases can be more expensive, more difficult, or too invasive to be performed. It’s not difficult to see how 3D printing is going to modify aesthetic and art processes in the future.

“Critical making” refers to the hands-on productive activities that link digital technologies to society. It is invented to bridge the gap between creative physical and conceptual exploration. The main focus of critical making is open design, which, in addition to 3D printing technologies, includes

other digital software and hardware as well. People usually reference spectacular design when explaining critical making.

Anthony Whitaker’s design is spectacular. He describes his main goals as, “I want to use 3D technologies to create an artistic expression in another tangible, fixed medium that will last into the millennium to extend critical reflection on 9/11 and our capacity to endure in triumph; in doing so, reconnect our lived experiences with art and conceptual critique. I feel like I was given this mission, and it’s my way of serving humanity.”