By Daniel Rose

In the Spring of 1963, our friend Bayard Rustin asked my wife and me to join him for dinner with Martin Luther King Jr, whose formidable “Letter From Birmingham Jail” we had just read.

Bayard was working with A. Philip Randolph, head of the Sleeping Car Porters Union, to plan a mass rally in Washington, D.C. later that summer to focus national attention on black unemployment and to call for a public works program providing jobs for blacks. Although Randolph was the leader, Bayard handled the logistics and Dr. King was to be the chief speaker at the Lincoln Memorial on the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

They were asking friends for help in raising working capital, which was going slowly because at first some major civil rights organizations, the NAACP and CORE among them, failed to support the event.

At the dinner, when I expressed fear that bringing together thousands of militant marchers could be counter-productive if they rioted, I was assured that the event would be serious in message but pacific in tone. My fear that hostile “Bull Connor-type” police might incite the marchers was answered with the reply that enough volunteer off-duty black policemen would be available to insure safety. And the President’s office had told them that National Guard and U.S. Army forces would be available if necessary.

The spirit of Mahatma Gandhi and Henry David Thoreau was invoked; and Dr. King spoke so fervently that we were deeply moved. At the time, I was a salaried 33-year-old with three children and a pregnant wife (Gideon was still in JSR’s tummy); and a cup of coffee and a hot dog each cost a nickel.

When I wrote a pocket check for $1,000 to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King thanked us warmly. He noted that of all the contributions of $1,000 or more he had ever received for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, some 90% had come from Jews involved in the Civil Rights movement.

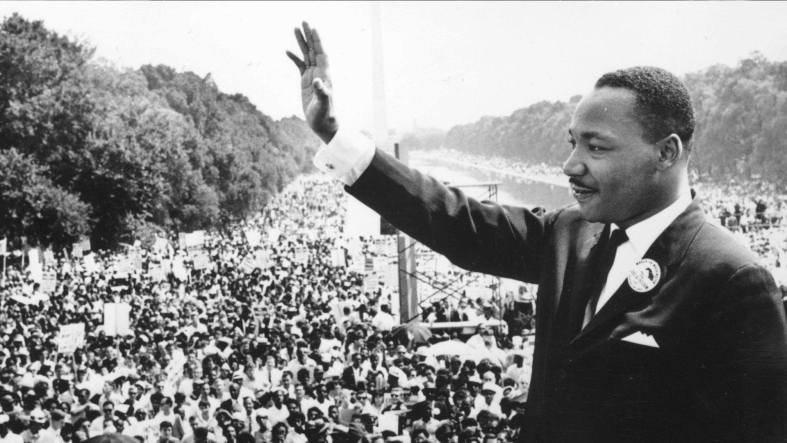

Soon after, the NAACP and other civil rights groups joined to support the March; 250,000 people attended; and Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech became part of American history.

The emotion generated by the 1963 March was a significant factor in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Act of 1965. And we are proud to have played even a modest role.

[Note by The Harlem Times: View the Original Draft of “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” and hear the Audio Recording of King’s reading of the Letter on the website for The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute (Standford University) ]