by Ryan Yablonski

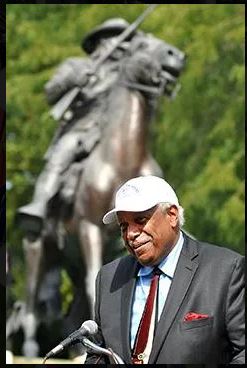

Commander Carlton G. Philpot, US Navy (Ret.) has become one of today’s leading historians of Black American military history. He has spent many years advocating in the White House and Pentagon for formal recognition of Black military heroes via medals of distinction and the creation of massive monuments and exhibitions across the country. In addition, Commander Philpot frequently conducts youth leadership seminars and uses his speaking skills to raise money and awareness for the sickle cell. He is a true icon of patriotism and advocate of the pioneering spirit of African American servicemen and women in our history.

A 24.5-year veteran of the Navy himself, Philpot’s military career was an experience he surmised as “You don’t always get what you want, but you get what you need.” Philpot was born to a military family in Florida. His father was in the Navy, his uncle was in the Army and he was an adventurous spirit that wanted to see the world as a Navy doctor. A valedictorian of his class who was not eager to fight in the War in Vietnam, Philpot went on to study medicine in college at Florida State rather than enlist. He graduated in 1962, which was during the early years of integration at college institutions. Among his peer group of prospective doctors he was the only one that got drafted during medical school not once but three times. He joined an officer candidate program but his classmates were skeptical; they asked him, “are you really going in to fight for the white man’s army?”

In the ‘60s, the prevailing notion was that the Navy was only for white people. Philpot, however, rose to the rank of Commander, which was unusual at the time. There were less than 200 Black commanding officers in the Navy as it was one of the last branches to aggressively seek integration of rank. Carlton recalls that Blacks had to work twice as hard and it was difficult for them to come up the ranks and get recognized for awards after their service.

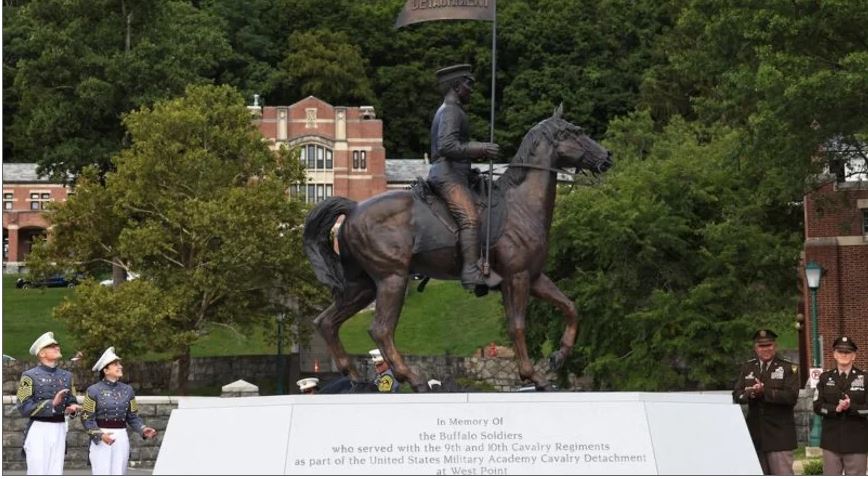

What followed was an unusual assignment as an instructor at the Army’s Command and General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Philpot was hesitant to accept the position at first, but it ended up being “the best thing that ever happened to me.” Working with General Dorty at Leavenworth he met with surviving members of the “Buffalo Soldiers” 10th Cavalry Regiment, who were not only the first all-Black U.S. Army unit but also legendary in their success and accomplishments. Philpot recalls being disappointed by the fact that their story was typical of the second-class treatment that Black military personnel had to contend with; yet, in spite of that, none of the soldiers were angry, and in fact they were incredibly proud of their legacy. He began connecting with like-minded people and secured $1.3 million of funding for massive statues and monuments to honor these lesser-known Black military heroes. This includes monuments commemorating the accomplishments of: General Roscoe Robinson, the first African-American four star general in the Army; Lt. Henry O. Flipper, the first African-American to graduate from West Point; BG Benjamin Grierson, the first officer assigned to the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldier Regiment; and the 555th, the first African-American Parachute Battalion in the Army. He is most proud of a monument honoring the all-Black Women Army Corps (WAC) unit, the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, which was dedicated on November 30, 2018. This unit was the first group of solely women of color to be deployed overseas, who became famous for their excellence and effectiveness.

For more than 30 years, Philpot has been Chairman and Project Director of the Buffalo Soldier Educational and Historical Committee. The committee’s primary objectives are to enhance the recognition and awareness of the “first-class” contributions of African American military units and individuals who have served this country with dignity, courage, bravery, and honor in spite of the “second-class” treatment and recognition received during and after their service. He is currently working on a project called “Walkway of Patriots.” Readers can learn more about his memorial projects and donate at www.womenofthe6888th.org.

“I don’t regret one bit of the Navy, the only thing I didn’t like was getting sea sick. Statistically Blacks in the military are doing better with investments and retirement than in the civilian world and service has allowed individuals, especially Blacks to do more, I believe.” After the Navy, Philpot became a professor at University of Saint Mary, Columbia College and Webster University. All in all, his favorite job has been his current: volunteering as a mentor in a job corps Navy ROTC program where he helps kids who did not fit in with the regular school system reach distinction in college and military careers. He says that seeing his students become success stories is greater than any accolade for a monument. “Volunteering shows the kindness of people and their heart, while teaching shows you the potential of young people and great responsibility to do something with it. I think that the hand of providence helped me learn to be a teacher.”