by Daniel Rose

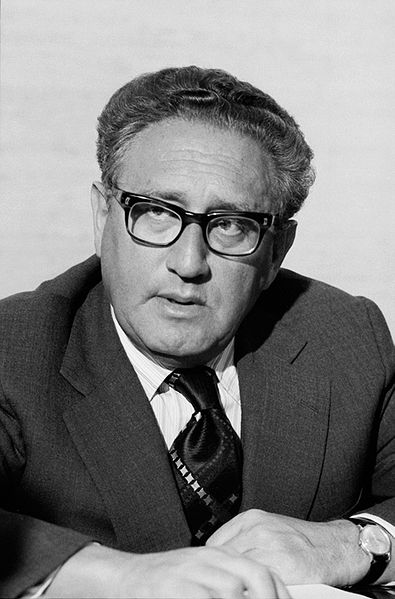

With the passing of Henry Kissinger, the United States has lost the important voice of our controversial but unequivocal spokesman for hard-nosed, pragmatic, self-interested international relations that served our national purposes.

Known as ‘Realpolitik’ by political scientists, the Kissinger approach focuses on what is realistically achievable and feasible, rather than on the ideal or even most desirable. Practical results were what counted to him; and ethics or morality, secrecy or duplicity, interested him only to the extent that their public relations impact were factors to be considered. Human rights and democratic values were secondary considerations, yielding to the search for stable international power relationships that diminished the chance of open warfare.

The London Economist has termed his position as “amoral realism shot through with idealism”; and in an interview shortly before his death he told the Economist that his life’s work was preventing a repeat of the wars of 1914-18 and 1939-45, and “today, that means keeping peace with China”.

In Kissinger’s most recent book, “World Order”, he wrote, “after withdrawing from three wars in two generations – each begun with idealistic aspirations and widespread public support but ending in national trauma – America struggles to define the relationship between its power (still vast) and its principles”.

Kissinger’s admirers are many, as are his critics, among whom are President Barack Obama. Mr. Obama has commented that he spent much of his presidency facing – and trying to repair – the world Kissinger left him. “We dropped more ordinance on Cambodia and Laos than on Europe in World War II”, Obama said in an interview in The Atlantic in 2016, “and yet, ultimately, Nixon withdrew, Kissinger went to Paris, and all we left behind was chaos, slaughter and authoritarian governments that finally, over time, have emerged from that Hell. In what way did that strategy promote our interests?”

To Kissinger admirers, he was the inspired architect of the Pax Romana. To his critics, he was responsible for the destruction of Neutral Cambodia and the rise of the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot, its savage dictator. No one, it must be said, questions the formidable role that future historians will ascribe to HK.

Henry Kissinger’s career – as scholar turned diplomat – is now complex material for historians to ponder. The question for the rest of us is straight forward: What lessons have we to learn from him? And many would reply:

First of all, dispassionate analysis of the real world factors influencing our prospects.

Secondly, “live and let live”. States must tolerate each other’s differing values, aspirations and practices.

Thirdly, the main threat to peace comes not from realists but from zealots.

Finally, analyze and tolerate military deterrence. What ultimately keeps the peace is the threat of war and the willingness to carry it through.

May our search for stability proceed without HK to guide us, and may the ‘powers that be’ act accordingly.