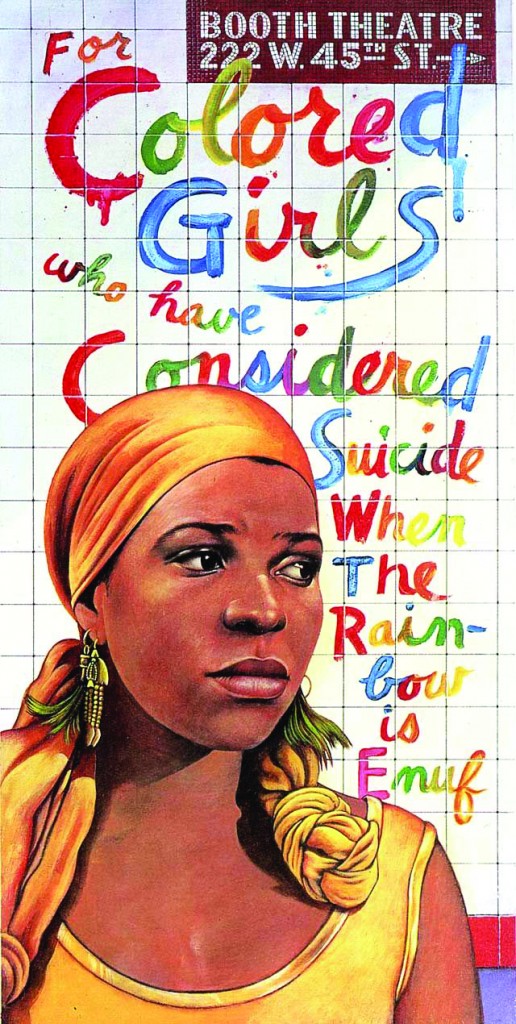

The 40th anniversary of for colored girls who considered suicide when the rainbow is not enough and the 100 YEAR ANNIVERSARY OF THE HENRY STREET SETTLEMENT

I believe it was Ms. Shange that suggested the outdoor area. A lone tree, graced with a full lattice of dark, green leaves shaded the area from the incredibly sunny afternoon. While waiting in The Abrons Center garden conjoining within the back of The Henry Street Settlement, I listened to the birds chirping noisily overhead. It seemed as if they were as excited as I. Ms. Ntozake Shange entered the garden attired in warm orange, burnt gold and amazing yellows. She and the Autumn day; both brilliant and vibrant.

Truthfully, I would have to write a book to devulge through all Ms. Shange has accomplished. Playwright, Author, Performer, Activist, Feminist and Professor, Ms. Shange’s various achievements encompass a history of geographical and professional voyages.

RM: What a lovely name. What does it mean and where does it come from?

NS: I wanted to have an African name during the Black Power movement. I wanted a name that wasn’t a slave name. I asked two South African exiles if they would name me. They observed me for four months and then one day out of the clear blue sky, they just came up and said, “We’ve got your name.” They handed me about twelve sheets of papers, with handwriting on it with the explanation of my name. When you digest it, it comes to mean, “She who comes with her own thing, who walks like the lion.”

RM: When did you actually become her?

NS: I didn’t start using my name for three years after I got it. I was sort of afraid of it. Then when I moved to Boston, away from Los Angeles, I decided it was time for me to take on my true writer identity, as Ntozake Shange. I didn’t like my given name as a writer. I didn’t want to be known as Paulette. I had people start calling me Ntozake, in Boston, in 1971. I felt freer.

RM: What is it like to be Ntozake?

NS: Well, I’m having a pretty good time now. I work a lot, I enjoy my friends, I pay attention to current events and affairs and disasters. I react to them. We are getting ready to start our 501 C, so I can teach creative writing to young girls in juvenile detention. Those are the kinds of things that I am thinking about right now.

RM: Why are you here at The Henry Street Settlement?

NS: I am here today to celebrate the 100th year anniversary of The Henry Street Settlement House. It is an artist based institution on the lower east side, here since the coming of the 20th century. It is offered to the downtrodden and the impoverished. The arts and the fundamentals of beauty and visionary(ness) that often escape us when we’re poor and don’t have access to great books, museums, or libraries, because our parents don’t know that that exists for us. Henry Street has been offering this to us for 100 years now. I am proud to have been part of the Henry Street tradition. “Colored Girls” was first presented at the playhouse in 1975. I am here also to celebrate Woody King.

RM: Also that means you are celebrating your 40th year anniversary of For Colored Girls…

NS: It’s amazing, I never thought I would live past 34, because Lorraine Hansberry died when she was 34. I didn’t think I would live beyond her because she was the pinnacle of success. So how could I possibly live longer than her? So it is amazing to me that I am still here and people still read my work. That I’m still writing and that people want to hear the new work as well as the old work. It’s just fascinating and just joyful.

RM: Did writing come easily to you? Why do you write?

NS: Yes. I started writing because I saw a picture of a little Vietnamese girl with all this rubbish burning around her and a white Barbie doll, with no cloths and one leg in her lap. That picture moved me so because, it was a child in the throes of war. A war I didn’t believe in and Black and Latino men were dying disproportionately in. It forced a poem out of me, the first poem I ever wrote. I published it in my high school literary magazine. I forget the name of the poem.

RM: Do you still collaborate with your sister?

NS: Yes. We are working on a reimagining of photographs of “Lovers In Motion”, which is a show I wrote 30 years ago. As a very young playwright, it had many flaws. My sister and I revisited the script and rewrote it and we think we fixed it now, so that it is a reflection of a mature writer. My sister directs it and I have new parts in there. We have a white character we never had before. That’s coming to NEC in May at La Mama.

RM: Do you still go to Barnard’s Reunions?

NS: Yes, I do. I am a Fellow at Barnard now, at The Barnard Center for Research for Women. They are teaching a course on me now. I have given them my archives, my archives are at Barnard and I am doing interviews and classes with students on a fairly regular basis.

RM: Tell me a little about The Columbia Rebellion and what if anything changed since.

NS: Oh my God! I had been at The Metropolitan Museum looking at a painting for an art history class. When I got back to school that evening, there were all these students in the yard at Columbia. They were going into these buildings, there was a huge ruckus and chaos. I went back to Barnard, and I understood that the Black students were in Hamilton Hall. I said to myself, “I have to get overt there”, but the gates were locked so, there is a ledge where the windows (very big windows) were even with the sidewalk. I went to one of the windows and jumped off the edge onto the sidewalk, went over to Hamilton Hall and snuck in. All my classmates, fellow Barnard students were there and Columbia students, we had been attending school for three years. We were demonstrating against the curriculum and against the administration’s capricious way of dealing with students. We wanted to have more student control and more influence about the courses we were taught. What happened immediately afterwards was a lot of people were injured and beaten by the police when they finally came to take us out of the building. A lot of people went to jail. Not a lot happened immediately in terms of our initials demands. In the next five-year period, after that, things did start to change.

RM: What was the best part of being in an all-female college?

NS: The best part was the continued reinforcement. The continuous nurturing and acknowledgement of female intelligence and curiosity.

RM: You have CIDP. Would you write about this challenge?

NS: I have written one essay in a book called, “In the FullnessTime of Time.” I have written one essay about it that I have incorporated into my next theater piece that I am working on in Cleveland. It’s called, “Lost in Language and Sound”. It is based on the essay from the book by the same title, as well as, some fragments of poems and other isolated essays I have collected together. These are an autobiographical look at how I became the artist I am. So, I examine my illness in terms of how it’s affected my creativity and my relationship to the world. Because it has. It’s made a big difference how I approach physical, tangible things, like stop signs, stairs, walls and sidewalks. I have to do that differently than I did before; when I was able bodied. It makes a difference when I am talking to people, cause, they can do things in casual conversation, that I can’t do. Like they can get up and walk and have a cigarette, and I can’t do that. They can pour a cup of tea and talk and I can’t do that. So, I am constantly aware of what separates me from the rest of the world by my illness. But sometimes, I am really lucky. I will be able to transcend the difficulty and just meld into a conversation or a situation with my spirit.

RM: You wrote a cookbook, called “If I Can Cook You Know God.” How did you find and put together all of these diverse recipes?

NS: I just had to explore my life. My friends in the kitchens. My friends that I have been gifted being feed by from all over the diaspora. So I was able to call them and get recipes from them. I had recipes from Uganda, Carolina, Nigeria and Philly. They are all in one cookbook because I wanted to tell our story, sort of through our food. Our food reflects how we use our time, what we value, and what our tastes were like, what we are yearning for. I think that’s why we spice our food, because we are yearning for freedom. In the spices, you find the freedom in cooking and find the freedom in food. That’s why I loved writing that book.

RM: You and Terri Williams have both been involved in the discussion of Mental Health. How important is this discussion in the Black community?

NS: I think it is incredibly important for us to have mental health services available to us on a regular basis at a reasonable pay. Because, our families are so fractured and our children lives are so compartmentalized. Because of technology and the physical realities of their families, it’s hard to mold and integrate the individual. To do that into young adulthood and all the pressures of being people of color and add to that poverty and violence, we are left at a disadvantage. So I think mental health services are of most importance to us. Any communities we design for ourselves, we should incorporate as is fundamental to our life style.

RM: Any recommendations on opening a child’s eye to the arts?

NS: Listening to music, listening to young poets, looking for new books, looking for new writers for your children to read or hear from. Reading books to your children. Having them play an instrument. Being involved in their daily activities, if they run, going to track meets. If they play football, going to that, if they play basketball, going to see that. Encouraging them in whatever they are inspired to do with their free time.

RM: Tell us about the award winning animated HBO animated series you created “Whitewash.”

NS: “Whitewash” was a story that really touched my heart. It was a very painful situation that actually occurred, in New York City. Two Black Dominican children were painted white by some white children. They were taunting and harassing them. That was a situation given to me by the illustrator. I was afraid at first because, I was afraid to feel the feelings the children must have had while they were experiencing being painted. I thought it might be too much for me. But as I came to know my characters better, I realized that they were resilient and they were compassionate with each other. They didn’t turn on each other with self-hatred with oh look what you look like. They turned to each other with love and sympathy for what had happened to them. Their classmates were resoundingly in favor of their nurturing after such a dastardly thing had happened. The whole school was supporting these two children that had been so humiliated and were heralded by the end of the book.

RM: You are a Professor of American Studies and Women’s Study. What is one of the major lessons you have learned as a woman writer?

NS: Not to edit yourself. I find that the thing that inhibits most women is that they can’t get rid of the second voice of approval or disapproval in their head. So even if they are writing in a journal, or a diary that’s private, it sometimes gets to a point where they ask, “well can I say that, what will people think, is that too angry, is that too revealing, am I too vulnerable”? When we start asking ourselves things like that we inhibit the creative process. So it is very important to get rid of the inside editor.

RM: In some of your poetry you openly address loneliness and sexuality.

NS: We are viewed historically as sexual beings and yet we are such puritans. It always seemed perverse to me that we would be the image of wanton lewdness and turn around and be afraid to have oral sex. Or be afraid to explore sexuality in different ways and shapes and forms, like the Kama-Sutra says you can do. There are all these different things we can do, and it is assumed we do them cause we’re Black. That’s the image of what Black women are and we deny ourselves that. We deny ourselves the right to pleasure ourselves. We deny ourselves the love of other women. We deny ourselves the love of multiple men, because of, I think, our recoiling from the stereotype and not wanting to be the stereotype. But we have real lives to live. Our real lives are not stereotypes. When we recoil from the stereotype and make that our real life; we are virtually erasing ourselves.

Readers and fans will be pleasantly surprised to know that starting this year there is a Shange curriculum at Barnard College. They also have a website called Shange World, where her scholarly articles are published.

It’s about time! So often school curriculums are dedicated to only dead and ancient Europeans. No disrespect. Still, new authors of all nationalities and Black authors and authoresses (living and passed) need their due curriculum, exposure and study, especially in Black, Latino and Asian American schools. In reflection, one can’t know where they are going if they do not know from whence they came.